Uefa will announce the list of host cities for Euro 2012 next week and everyone wants to keep hold of their slice of the financial pie.

These are a big few days for Ukrainian football. On Thursday, they will find out who will be their first representatives in a European final for 23 years, as Shakhtar Donetsk host Dynamo Kyiv in the second leg of their Uefa Cup semi-final, a 1-1 first-leg draw having seemingly handed Shakhtar the initiative, even if they were second best for much of the game. Then, next Wednesday, Uefa will reveal the confirmed list of host cities for Euro 2012. After all the criticism and all the doubts, this will give a sense of finality.

The criticism and the doubts are justified. Both host countries suffer chronic, almost institutionalised, corruption. Poland have a poor football infrastructure but decent transport; Ukraine has poor transport but good stadiums. Both have work to do on airports and hotels. But it does seem that this is going to happen. After a Uefa inspection in February, Hrihoriy Surkis, the head of the Football Federation of Ukraine, said he had breathed a sigh of relief. The mood had changed; Uefa, after numerous warnings, was content with the progress it saw. It should be noted, though, that it has given itself until September to change the host entirely.

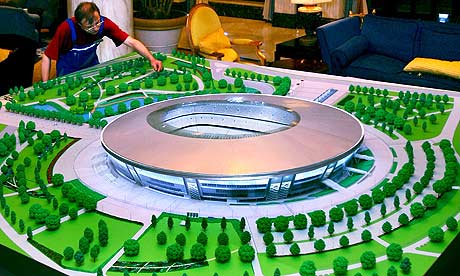

A model of new UEFA-standard stadium soon to be completed in the east Ukrainian city Donetsk, one of the expected host cities for Euro 2012. Photograph: Photomig/EPA

Still, though, there are question marks. The initial plan was for four cities in each country to host games: Warsaw, Gdansk, Chorzow and Wroclaw in Poland and Kyiv, Lviv, Dnipropetrovsk and Donetsk in Ukraine. Michel Platini, though, has warned that he will name “between six and eight” cities next Wednesday, and that they might not be evenly distributed between Poland and Ukraine, the implication being that Ukraine could be relieved of some of its hosting responsibility.

And then there is the subplot of the reserve venues. It seems unlikely that either Kharkiv or Odessa could nudge into the frontline of the Ukrainian reckoning, but Krakow certainly could displace one of the Polish front-runners (presumably Chorzow, which is only an hour away and behind schedule). Given the success of Wisla, the local club, over the past decade, and the excellent tourist infrastructure in the city, it seems bewildering that it was not first choice to begin with – and who, after all, wants to spend three weeks stuck in what is effectively a suburb of the grimly industrial Katowice, when they could be in a thriving town full of historic sites, lively bars and excellent restaurants? Poznan, equally, has a realistic chance of replacing Gdansk.

In Lviv, which for a long time seemed the least likely of the Ukrainian venues, there is quiet confidence. The head of the regional administration, Mykola Kmit, is an impressive figure, largely because he admits the problems and explains his solutions. That may not sound like much, but after the cloud-cuckoo drivel that has spewed from other administrators connected with the tournament, it is an encouraging novelty.

He, of course, puts the case strongly for Lviv. It was, he points out, where football was first played in Ukraine. It’s a compact town. It’s the closest potential host to Poland and has good transport links. In 2008, 2.5m tourists visited Lviv: the estimated extra 300,000 or so for the Euros shouldn’t place too great an additional strain on the infrastructure (and, frankly, 300,000 sounds high). When Pope John Paul II visited Lviv, it is estimated there were over a million visitors, and the city coped then. Kmit is thinking only of expansion. “Our target is to have 8 million visitors a year,” he said. “Krakow has nine to 10 million a year and Lviv is often compared to Krakow.”

Which is all well and good, but Lviv differs from Donetsk and Dnipropetrovsk in that the tourist infrastructure there is far less of an issue that the stadium, the building of which suffered a series of false starts. The Austrian company, Alpine BAU, initially contracted to build it withdrew. “The Austrian company had signed the paperwork for the project development, and there was a clause in the contract that if they liked they could become a developer and an investor in the project, but they were asking too high a price,” Kmit explained. “So we will pay them for the work they have done, the design, and we will build it with another company.”

That company, Azovinteks, has no specific expertise in stadium construction, which raises obvious concerns, but as Kmit says, they have completed a number of complex engineering projects, particularly in metallurgy. And, of course, they are a Ukrainian company: the investment in 2012 is being returned to Ukrainians. Whatever else the European Championship in three years is, it is an opportunity for Ukraine – and to a lesser extent Poland – to haul themselves out of the economic crisis.

And the crisis, of course, is, on top of all the other worries, the real problem. A recent BBC report said that no European country was as close to complete economic collapse as Ukraine, and the fact that their government felt the need to apply to the IMF for a $16bn loan – which was turned down – gives some indication of how critical the situation is. Which, of course, raises the question of just how much of the 1bn Hryvnia (£83m) needed to redevelop the airport or the 180m Hryvnia (£15m) required for the stadium construction it’s going to be possible to raise from national and regional government or the private sector within Ukraine.

The positive way to look at the situation, though, is to view the tournament not as a burden, but as a tremendous stimulus. “If something has to be cut, it will not be Euro 2012,” says Kmit. “From my point of view this is a great opportunity, because you’re spending into development, which should stimulate growth. 2012 will lead to increased tourism, not only to Lviv but to all of the Ukraine.” Certain ambitions have been scaled back because of the financial crisis: there will, for instance, be fewer hotels, and fewer new border crossing points – but then, there are likely to be fewer visitors, so there is in a sense a natural balance.

The road will not be smooth. There are likely to be further crises ahead, and the chances are that 2012 will not be an easy tournament for fans or journalists. Part of the rationale behind awarding the tournament to Poland and Ukraine was to reach out to eastern Europe. That is even more important now than it was when the decision was taken. Perhaps 2012 will at times feel like an ordeal, but it will at least be for a necessary cause.